The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

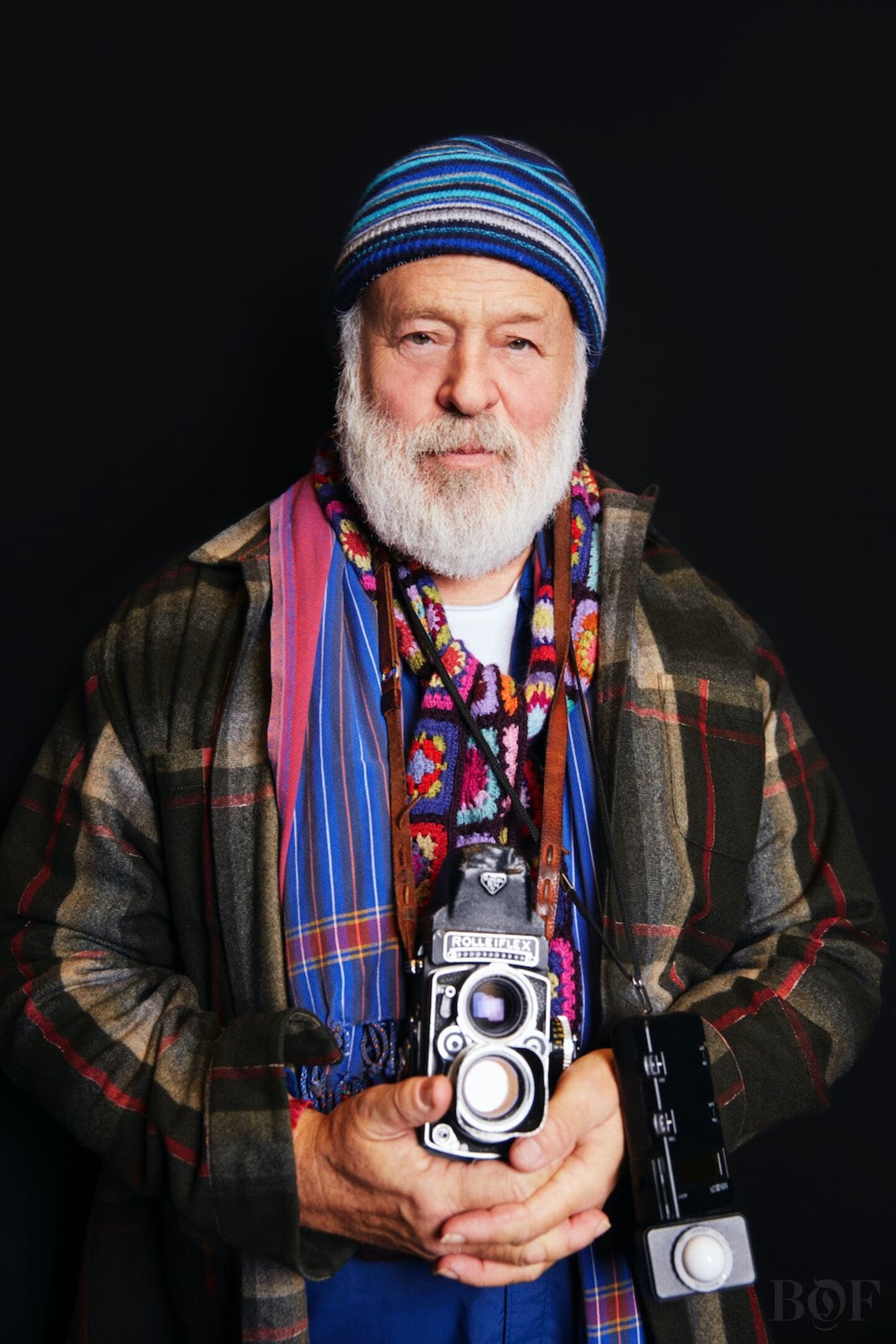

“It’s a bit of a circus with me,” Bruce Weber says over coffee in his Manhattan studio and archives. A swiftly setting winter sun fills an enormous wall of windows with dramatic blues and purples, but inside all is warm and calm. The regular retinue of assistants, producers, handlers and subjects who accompany him during his work — an amorphous clan that can include full marching bands, jugglers, elephants and specimens of rare beauty — that circus, has decamped after a long day.

Only Weber’s beloved golden retrievers, padding in and out, now listen to us talking about his work. “People think that photographers live like their photographs,” Weber says. “In some way they do — emotionally. But physically they don't. I'm always with a lot of people in my pictures. But I don't have a lot of people around me a lot in my life.”

Weber was born in 1946 and raised just outside of Pittsburgh, in the coal-mining town of Greensburg, just then beginning to swell as it welcomed home its veterans from World War II. The family was close — Bruce’s grandparents lived next door, his aunts, uncles and cousins nearby — but not often good company. When the drinking and the shouting died down, if it did, something the whole family could agree on was the pleasure in picture taking and Weber spent many a Sunday making 8mm films in the backyard with his father. At night, he would tune into the broadcast of pioneering DJ Alison Steele — widely known as “The Nightbird” — imagining, as he did, having a love affair with Steele, who spun rock and roll from a studio in Manhattan while chain-smoking Nat Shermans as her champagne-coloured poodle cuddled in the cords.

Any good photographer has to have a fantasy life other than their own.

But if Steele was Weber’s first crush, his greatest early enchantress was his worldly and popular elder sister Barbara. It was Barbara who turned him on to the romance of Capri, to Broadway musicals and, later, when she was booking musical acts in New York, to the dazzling power of David Bowie and Iggy Pop — as well as to one of his first jobs, shooting Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention on tour. And if Weber’s real world circus has a real world inspiration, he says, it is Barbara. “My sister had lots of friends. I didn't have that many friends, and I was kind of alone, so I would go to her parties and hang for a little bit, and then I would go up to bed. Everybody would be smoking joints and having a great time, and I was just a young kid — this really awkward, nerdy kid. So I didn't really have that life. But I knew how to imagine it. I think any good photographer or director has to have that — a fantasy life other than their own.”

ADVERTISEMENT

His fantasy life is everywhere in evidence around him now. The whitewashed walls of his studio here are stacked high with photographs that Weber has collected over the years, most of them black and white, many of them portraits of the glamorous midcentury demimonde, of Marcello Mastroianni, of Jean-Paul Belmondo, of Richard Burton with (Weber’s great friend) Elizabeth Taylor. Burton and Taylor are everywhere, in fact, in dozens of photos, but only as their better, marvelous angels — on set, on yachts, in bed, in publicity stills — not as the boozy, bloated, unfaithful squabblers. And this elision of grubbier reality, as well as the countervailing celebration of mythic and nostalgic glamour — print the legend, the whole legend and nothing but — is fundamental to Weber’s fantasy land: an enchanting playground inhabited only by heroes (everyone Mark Antony and Cleopatra, never just Dick and Liz) and an exotic spectrum of heroic beasts.

So vivid and consistent is Weber's theogony that it seems to exist, perpetually, in parallel to our experience, as a kind of mythic continuum, maybe the most celebrated motif of which — and no small part of why Weber will on December 5th be honored by the British Fashion Council at its revamped Fashion Awards — is his signature elevation of men and the male form to the divine.

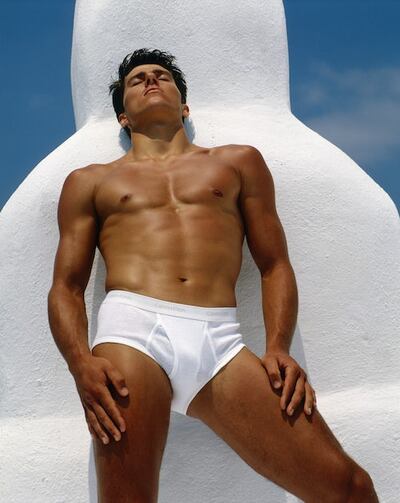

From his earliest work, Weber had a reputation for, as the photography critic Vince Aletti put it, of “turning jocks into demigods.” Weber’s photo of the pole-vaulter Tom Hintnaus in Calvin Klein briefs occupied the place of pride in Times Square in August 1982, and then in popular consciousness ever since — “a colossus looming over a crossroads,” Aletti wrote, which “made Weber the most visible iconographer of the 1980s and established his particular type of buff beef as the new all-American idol.” And Weber’s all-American idols are still the ideal, the apex of masculinity and male beauty — an accomplishment that is impossible to overstate, so powerful and present is his mythology in the public imagination.

It is also worth noting that Bruce’s male gaze on the (notably, straight-seeming) male form, is in itself a kind of revolution in our visual lexicon, a tradition of representation in which women are almost always depicted sex first, while men are rendered with their personalities at the fore. But, with Weber’s pictures, personality is almost always enveloped by the greater, ongoing myth-making.

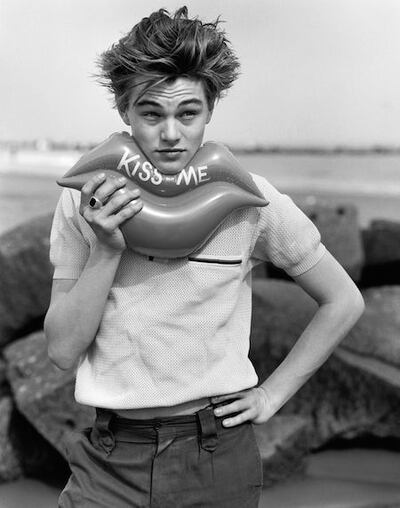

Even when he is shooting high-wattage celebrities (as he has done for Vanity Fair, GQ and, with his longtime collaborator Ingrid Sischy, at Interview, where he made those very famous portraits of Leonardo DiCaprio, River Phoenix and Mark Wahlberg, among others during the 1980s and 1990s), when Weber shoots them, they seem less like stars of the screen than stars of his world, on equal footing with the wrestlers, cheerleaders or Labradors he surrounds them with.

“I might drive somewhere,” he says, “and on the way there see something, or meet someone, and I’ll take them along. But the sad thing is that it’s changed a lot. You don’t have that same freedom to be so open. It’s always humourous to me that publicists want to know what the photos are going to be. How do I know if I haven’t met the person yet? I think you have to fight, dig deep, to find it. And I think you get yourself into situations where, you look for an experience, and, if you’re lucky, you have one. You put that experience into your work, and then it’s special for you.”

Something that feels special to Weber, apparent especially in his commercial work, is a very specific kind of Americanness. In the same way that his subjects' clean-shaven square jaws, dimpled chins and gym-toned torsos correspond directly with (or actually have in part created) our idea of jocky Midwestern males, the signifiers in many of Weber's most famous stories, for Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren or Abercrombie & Fitch — the frequent cowboy hats, occasional cans of beer, the Adirondack lakes and ubiquitous golden retrievers — all have a heartland BBQ feel about them (his passion projects, too, pursued on his own dime and time, often come together in editions of his journal fittingly called All-American). In this corner of Weber's fantasy, it is always summer, every man looks like Montgomery Clift, letterman jackets go with everything and buoyant camaraderie and optimism rule the land — which is of course what makes him so enormously valuable to brands selling that very idea.

Bruce Weber art directed a country. A great deal of what I think of as America is actually Bruce Weber's idea of America.

"Bruce Weber is the most influential fashion advertising photographer ever," says fashion journalist Jo-Ann Furniss. "As Alasdair McLellan pointed out, 'Bruce Weber art directed a country.' And a great deal of what I think of as America, is actually Bruce Weber's idea of America, an idea he has expanded on through his commercial work with Calvin Klein, Ralph Lauren and Abercrombie & Fitch." We could expand this to include the Detroit-based brand Shinola with whom Weber has been collaborating for the last couple of years (and this is to say nothing of his indelible work with Versace).

ADVERTISEMENT

“When people hire me to photograph for them, I think about the person I’m working for, not the company,” Weber says. “Like, for instance, when I first started working for Calvin Klein, Calvin was out all the time at clubs and parties, he had this really glamorous New York life. In a sense, that’s what I was photographing — his desire, the passion he had to live like that. When I started working for Ralph, I got to know his family and it really started with family photographs. Ralph and I had a lot of common interests — in cars, old clothes — so I was photographing his world. It wasn’t my world, but it was his world. And that was the fun part of it, to go into these other worlds.”

It’s an awesome thing, to have so profoundly shaped the iconography of a part of America — and it makes one wonder what that national identity means to Weber, especially now that America itself has become drastically less hopeful, fuelling the rise of a populist figure like Donald Trump. “I do see America very differently now,” he says. “I've been travelling a lot because I knew the election was coming up and I wanted to see what was going on in the country. We were down in West Texas for a long time, in Kentucky, in Tucson. I could see how that whole part of America had changed, how disappointed a lot of people were with their life and their life in America. And so if I kind of interpret that, and eventually put it in my pictures, I'll find a way to get back to the way I originally felt about the country.”

[Post-Trump] I do see America very differently now.

In 1966, after a couple of years studying art at Denison college in Ohio, Weber transferred to New York University, looking for various media through which he might uncover his fantasy world, already then strong and growing. “I wanted to be in the theatre, but I also wanted to be in the art department and learn how to paint and draw,” he says. “I really loved writing then, and I read a lot… I think I also wanted to be a DJ, since I loved music so much.” It was at this time that Weber’s father cut him off and he began living what he has at times characterised as a “James Dean existence,” blowing all his money on a trip to the Virgin Islands, trying to get work as a model and chasing down some of his artistic heroes from whom he might get some direction.

“I had the great chance of meeting and getting to know Diane Arbus, and she always said to me something like, ‘Hey, don’t let those things cut you — your mistakes or your triumphs, if there are any.’” Following in Arbus’s footsteps, Weber began seeking out singular New York characters (addicts, amputees and an aged Russian princess; his first show, in 1974, was a series featuring runners up in a bodybuilding competition) who he began photographing with his now signature tenderness. After a stint casually assisting Saul Lighter and soliciting some further advice from Richard Avedon, Weber studied with Lisette Model at the New School, began testing, taking actor’s headshots and even got assignments shooting men’s fashion for GQ and Menswear magazine.

In the late 1960s, Weber first met Nan Bush who was running Francesco Scavullo’s studio, and the two became friends. At first Bush lent Weber film to shoot with, then she began championing his work, and then representing him formally, getting him bigger and better assignments, and eventually producing his shoots, arranging and maintaining the circus. In 1973, they moved in together.

And in all the time since, the circus Bush and Weber have built together has only grown larger and more inclusive — his subjects, his assistants, casting directors and creative directors, many of them, like Weber, former models, fellow seekers and fantasists, function as a kind of human satellite dish, amplifying Weber’s wonder and expanding the scope of his seemingly insatiable curiosity.

“When I go to LA for work now,” he says, “I always have a party at the end. I have babies; I have people who are 95 years old. A lot of people, especially in the film business, who only go to parties with other people in the film business, say, ‘How do you know these people?’ I say, ‘I meet all different kinds of people.’ I have drag queens there, I have football players. Hockey players. It’s crazy, but it’s the way my life is. It’s a little bit like my sister’s parties were, and it’s the way that I can feel what that was like, what I missed.”

The preferred lensman for the new Gucci talks collaborating with Alessandro Michele and why he decided to open a hotel in Venice Beach.

“I love women. I have a lot of respect for women and find them more interesting than men. The person I am drawn to is intelligent, strong and beautiful. Women are the main reason I became a fashion photographer,” says Hans Feurer.

In an era of ubiquitous digital imagery, several fast-rising fashion photographers are shooting film to differentiate their work, regain control over their craft and find a more human pace.

In an exclusive extract from her new memoir ‘How to Make Herself Agreeable to Everyone’ the model and activist examines the dark side of the industry — and her complicity in it.

Brand architect and art director joins BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss the philosophy that underpins his groundbreaking retail and hospitality concepts.

Avery Trufelman, host of the fashion podcast “Articles of Interest,” joins BoF founder and editor-in-chief Imran Amed to discuss the multi-faceted layers behind the aesthetics of fashion.

The award-winning director of ‘High & Low: John Galliano’ tells Tim Blanks why the designer doesn’t expect forgiveness but would love a little understanding.