The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

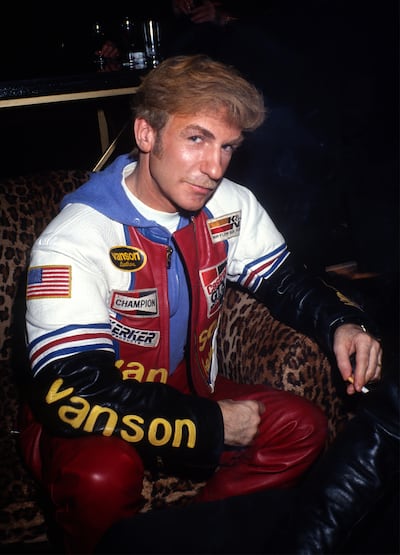

At 10 o’clock on Friday morning, the crematorium at Père Lachaise Cemetery in Paris will consign Claude Montana’s mortal remains to ash. It’s a sad end to a story whose extremes of triumph and tragedy feel like they belong to another time, another place, a fashion industry we scarcely recognise.

But the conspicuous squandering of tremendous talent will always resonate throughout our industry and every other industry that employs extravagantly talented, deeply flawed people. Sure, money talks louder than ever, but if it’s a story you’re after, wouldn’t you rather listen to Lee McQueen’s? Or John Galliano’s? Or Claude Montana’s?

In the late 70s, Montana re-defined French fashion with his linebacker silhouettes cut from black leather, fearless in the face of accusations of fashion fascism. In the 80s, he softened the shoulder, perfected a cut so precise that it left even the master Yves Saint Laurent so breathless he insisted Montana was the only designer he could ever imagine taking over his house.

Montana always represented fashion in its most distilled form, sculpted minimalist purity. But at the same time, he was unhinged by his quest. Bobby Butz, who lived with Claude for 15 years, remembers him torturing himself after every show. “Was it too simple? It could never be too simple. That’s what he was afraid of. He wasn’t going to do little shift dresses. People didn’t come to him for that.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The consummate irony of Montana’s story is that, while his professional life was a quest for purity, his private life was a mess of drugs, drink and degradation, culminating in his wife Wallis’s suicide in 1996. Butz had already given up a year earlier and gone home to New York to protect his own sanity. “A bad story, but probably a really good movie,” he acknowledges wearily.

Montana marked everyone who came close. Stephen Jones made his hats for 17 years, from 1985 onwards, all the women’s and men’s collections plus the five seasons of haute couture that he designed for Lanvin in the early 90s, the years that Jones considers the pinnacle of Montana’s career. “Each meeting was a lesson in geometry and precision of cut, the like of which I had never experienced,” Jones says now.

He arrived as the designer was establishing his own modern New Look, following on from the exaggerated drama of the early years that shaped his reputation. “The hats were showpieces, discreet, mannered accents, sometimes just a line, like an Antonio [Lopez] drawing, reduced to absolute simplicity.” Sometimes they weren’t even hats. “It being the 80s, Claude liked a big hairdo so hats didn’t always fit. But he was incredibly faithful. He would say, ‘I’m not really feeling hats but I would love you to make something to go with this… I’m doing a section in aubergine, what’s the most beautiful aubergine you can think of?’ I’d say, ‘Shiny’ and he’d say ‘Show me something.’” So Jones would end up making bodices, backpacks, collars, jewellery. He recalls nights when Linda, Yasmeen and Christy would wait patiently while Montana fitted a jacket to them, or draped them in a bodysuit embroidered by the maestro Lesage to flow like sand.

Each meeting was a lesson in geometry and precision of cut, the like of which I had never experienced.

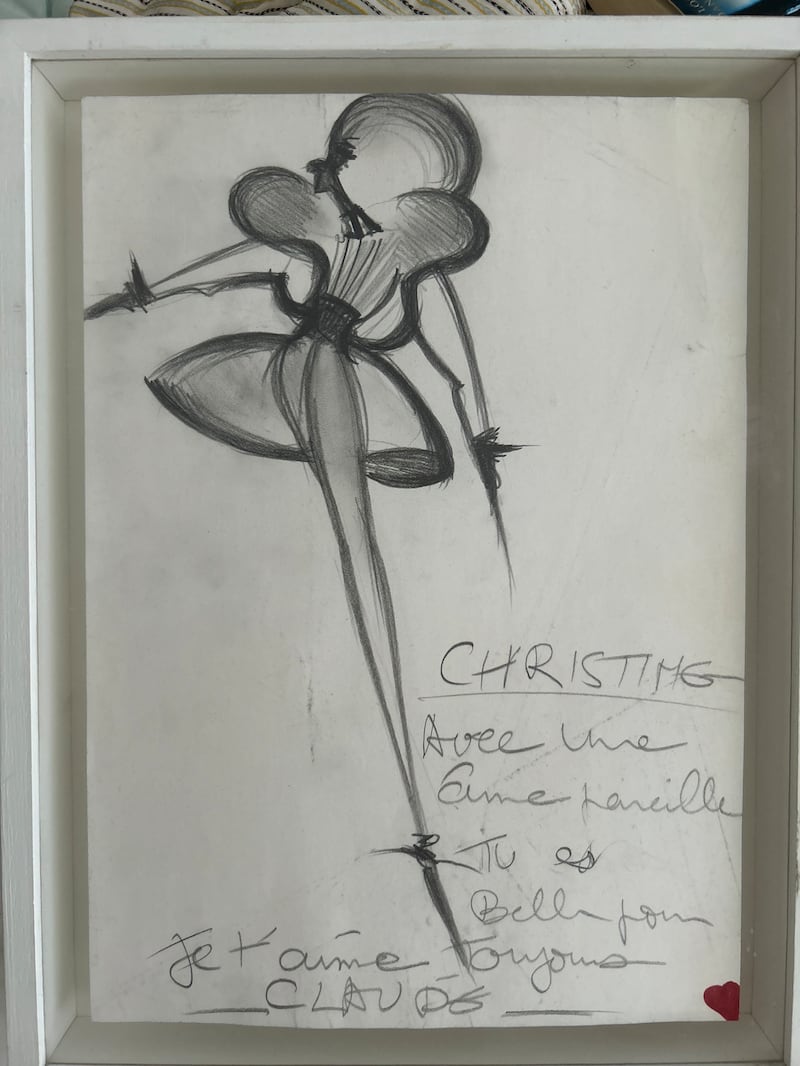

Statuesque blonde Christine Bergström remembers her own “five divine years” working with Montana as a fit model and as one of the most fabulous of his imperious catwalk queens. “We were very close in a work way, because the work was so demanding, we couldn’t be best friends as well. When I worked for Azzedine [Alaïa], I’d just stand in bare feet and he’d sew the dress on me. But with Claude, it was full hair and makeup. You’d pose in high heels in front of a huge mirror and when you were doing the fitting, he’d literally walk next to you and pose, almost the way you were supposed to pose. It was incredibly camp.”

You might wait anything up to two hours for the privilege, but anyone who had the good fortune to experience one of his shows in his late 80s/early 90s heyday appreciated the power of the pose for Montana. His groups of Amazons moved at a glacial pace. At the end of the catwalk, they would assume a position… and hoooooold it. “There was a sense of drama, you couldn’t just slouch down the runway,” Bergström remembers. “And it was all staged by Claude himself. Every girl had fittings of everything. There was nothing last minute. He had a very precise idea of how he wanted his clothes to be shown.”

And he generated his own star system. Irish model Aly Dunne, who could re-articulate her limbs like a startling hybrid of human being and praying mantis, is now one of Malibu’s most successful real estate agents. The wondrous Claude Heidemeyer seems to have vanished off the face of the earth, a fate which would suit her supernatural beauty. And Betty Lago, perhaps the ultimate Montana model, died in her hometown Rio at the age of 60 in 2015.

Montana’s precision also found expression in his distinctive use of colour. From 1991 till 1999, Karin Gruber worked with Montana, initially as a colourist and textile designer. She managed to make the transition from his arch rival Thierry Mugler. (Jones wasn’t so lucky. Mugler closed the door on him forever the day he agreed to also make hats for Claude.) Gruber worked on Lanvin with Montana, and, nearly 20 years later, found herself in exactly the same studio working on Lanvin with Alber Elbaz. “I could see he was using Claude’s couture collection from 1991/92, the tailoring with the integrated jewellery, as inspiration. He loved the way it worked. It was a very strong moment for him, but I think it was difficult for him too, because I was there and he knew what we had done, where we bought the fabric. He was a little bit intimidated.”

After leaving Montana, Gruber also worked with Tom Ford at Saint Laurent. Her experiences with Mugler, Ford and Elbaz, among others, highlighted one of Montana’s major shortcomings. “He didn’t have a global vision about a collection or a show. His team was a real family, the 15 or so people he had around him, and he trusted them. He waited for their proposals. How are we going to arrange the hair, the makeup, the accessories? He was very focused on the clothes. When he had fittings, he knew exactly what he wanted. But the hair, the makeup people, we’d be waiting for him for hours. There were times when he wouldn’t show up at all. You never know when people who take drugs are going to wake up. Sometimes, it really wasn’t easy. But when he was doing a fitting, it was incredible. It was not 1 mm; it was a fraction of 1 mm. More precise than Mugler, but no global vision.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Bobby Butz agrees. “It was just about the moment, making fashion, making it perfect. At the beginning, there were just five of us putting on those shows. Claude never had that huge vision.” Unfortunately, he also insisted on running his company, and he was, from all accounts, a terrible businessman. Monsieur Rouet, who had helped Christian Dior with his licences, tried to do the same thing with Montana, but the closest he came to the pivotal role played by, say, Pierre Bergé in the career of Yves Saint Laurent was his communications director Béatrice Paul, who struggled to keep her head while all around were losing theirs. By 1994, she’d had enough. When she quit, it was the beginning of the long death of Montana’s business: the sale and resale of the company, the loss of his name, the last sad show in 2002.

“His high point was Lanvin at the beginning of the 90s,” says Jones. “I was actually with him when he went to meet the managing directors of Beecham Pharmaceuticals in London. They owned the Lanvin perfume licence at the time and, by extension, Lanvin. They wanted him to do couture and ready-to-wear and he told them no designer could design two ready-to-wear collections — his own and Lanvin’s — at the same time. To do the best job, you have to give all your energy to one collection. I remember him saying in the car on the way back, ‘It’s just not possible for a designer to do it.’ Look at Tom and YSL, John and Dior, Lee and Givenchy. Claude was right in a way.”

In five seasons of designing couture for Lanvin, Montana went from being slammed (Suzy Menkes’s eviscerating review of his first collection for the International Herald Tribune set the tone) to being praised to the heavens. (He won the Golden Thimble for best couture collection two seasons in a row). But he was fired over his non-negotiable refusal to design ready-to-wear for Lanvin. It wasn’t because he was $50 million over on costs. “He was given an unlimited budget,” Jones insists. And it had nothing to do with alleged abuse of staff. Bobby Butz steams at the idea. “I will tell you one thing about Claude. He treated the ateliers so incredibly, he couldn’t have been nicer and more respectful to Lanvin’s and his own.”

“His whole thing was never to sell out, to be true to his aesthetic,” Butz continues. “In 1980, there was an offer on the table out of New York for 30 pairs of jeans for $30 million, and he wouldn’t do it because that would mean he was selling out. He was always afraid to go out and become, I don’t know, another Halston or something awful. He stayed true to himself, and it hurt him.”

Also hurting him, Butz suggests, was Montana’s relationship with the press. He never courted them. Awkward to a fault, he was an awful interview, and he maintained that his obligatory appearance at the end of a show made him feel stripped to the bone under hundreds of judgmental stares.

After Wallis Franken Montana’s suicide in May 1996, the subsequent media coverage of Montana’s presumed complicity in his wife’s demise was enough to result in a cancellation so comprehensive that neither Montana nor his career really recovered. “Shockingly so, because he still had a huge talent,” Jones says. Immediately after his death, journalist Dana Thomas published a piece on Substack that she had originally written for The New Yorker in 1996. Then-editor Tina Brown killed the story when Vanity Fair scooped them with Maureen Orth’s account of Wallis’ last days. Both articles painted a grim picture of a vibrant but fragile woman driven to kill herself by her husband’s abuse.

Thomas’ decision to publish so soon after Montana died reanimated the cancellation by casting a dark shadow over all the postmortem appreciations. It’s clearly rankled Montana’s faithful few. “There’s been so much crap written about Claude and Wallis,” Jones hisses. “They were absolutely best friends, she was completely inspirational to him, and they adored each other. I thought Dana’s piece was hugely inaccurate. Claude and Wallis were in love. It was an unhealthy love, but they forgave each other for their shortcomings. I think they were both in their own ways quite destructive people, but one was not worse than the other. In a way, you could almost say they saved each other, because even through darkness they understood each other, and sometimes, not always, were compassionate with each other.”

“Their relationship was very honest,” Gruber agrees, “but it was totally destructive. I liked Wallis but she was totally lost.” When Bergström heard about Wallis’ death, she thought it could just as easily have been Claude, or his sister Jacqueline. “I was kind of the fourth wheel, I spent a lot of time with them. But they were in a spiral, the three of them. None of them was good. I was close to Jacqueline as well, but it just got out of hand.”

ADVERTISEMENT

So what went so terribly wrong? Everyone agrees that cocaine was a key factor. Bergström remembers a time when Montana didn’t even drink. “He was far too sensitive. But it was all or nothing for him. When he started taking drugs, he just went mad.” She assumes it was a kind of self-medication for something buried deep and dark in his past that came back to haunt him. Aside from his sister, there was no blood family to speak of in his life, or even in his death. Others point to a profound melancholy that seemed to preclude true happiness.

For the past few decades, Montana lived as a recluse in his apartment near the Louvre. Occasional sightings, often with him in a state of disrepair, earned him the sobriquet “The Phantom of the Palais Royale.” In 2008, he was brutally mugged by a hustler and spent almost a year in hospital. Jacqueline was his principal carer, but, after she died four years ago, Karin Gruber and another Montana/Mugler alumna Isabelle “Zaza” Monzini became the designer’s lifeline.

Last October, when it became clear that he was no longer capable of looking after himself in his second-floor walk-up, he was institutionalised. There have been reports that he was in the grip of Alzheimer’s disease. Gruber disputes that. “He could remember everything from his work. Surrounded by photos of his shows, he could recognise each photo, each model, each season. He could tell stories about the fittings, the fabrics.”

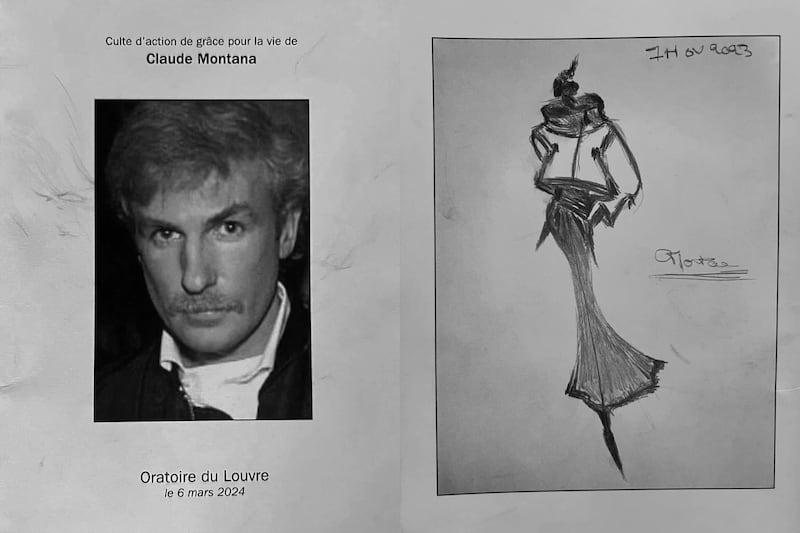

In the institution, Montana started to sketch again. (His last sketch was reproduced on the back cover of the memorial programme). Over Christmas, he fell and was hospitalised. “The last time he spoke to us about his professional life, he remembered the good things,” says Gruber. “But I think he accepted that sometimes he didn’t make the best decisions, and he was not very helped by the people around him to escape from drugs and alcohol.”

Montana’s memorial service two weeks after his death was conducted in the Oratoire de Louvre, ironically the same place where his rival Thierry Mugler had his send-off. (They were both Protestant). Mahler’s 5th Symphony opened the service, Diana Ross’s “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” closed it. There were 200 attendees: ex-fashion directors at Le Figaro, Jack Lang, the former Minister of Culture, now in his mid-80s, Béatrice Paul, Bergström, Gruber, Zaza Monzini and other people from the studio, 25 years on. “There really was a Montana clan, like the Halstonettes,” says Jones. In fact, when Gruber and Monzini visited Montana in hospital just before he died, he greeted them with a cry of, “Ah, the Montanettes.” The gathering was on the small side for such a significant figure. Nevertheless, Jones insists, “People were remembering wonderful times. There’s been so much bad printed about Montana that this really was a celebration of his huge talent.”

The last chapter compounds everything that has come before. No family members were at the memorial. The loyalists from Montana’s studio covered the costs. In December, the contents of his apartment — art, furniture, memorabilia (including a dozen pairs of handcuffs) — were sold at auctioneers Drouot to provide for his institutional care. The sale was unpublicised. It reaped a meagre $225,887, nearly $100,000 under the low estimate. PR maven Lucien Pagès bought the documents de travail, the work books for every collection from 1978 to 1999, including Lanvin couture, and 142 videotapes which cover every collection — women’s and men’s — between 1980 and 1998. He intends to have them digitised and will then donate them to one of Paris’ fashion museums.

But million dollar questions dangle. What happened to all of Montana’s money? Where are his archives? Bergström believes they were in a storage unit. “But the unit is empty. Maybe it wasn’t paid for. The clothes just disappeared. So much leather, fur, incredible innovations in knitwear just gone. And while there’s none of that it’s very hard for him to exert any kind of influence over people now. People need to see things, touch things.”

Another question: every time there’s a huge shoulder on the catwalk, there’s usually a mention of Montana but, given his decade-straddling importance, why has no one ever attempted to resuscitate his brand, especially when so many others, including his immediate peers Mugler, Alaïa and Gaultier, have had a successful second life?

Lack of access to any substantial physical legacy might be one reason. The cancellation is another possibility. “Bad juju,” Butz calls it. Then there’s the thought that he might just have been so completely of his time that there is no room for him in the modern world. His influence has filtered through, in the work of huge fan Lee McQueen, for example, or Riccardo Tisci or Joseph Altuzarra, but maybe there’s no longer a place for his brand of obsessive perfectionism.

Meanwhile, as we ponder that imponderable, Karin Gruber and Zaza Monzini will be at Père Lachaise on Friday, loyal to the end. “We can’t leave Claude on his own,” sighs Gruber. “It feels like we are still with him.”

The designer, who died on Sunday, was an icon of a golden age in fashion.

Tim Blanks is Editor-at-Large at The Business of Fashion. He is based in London and covers designers, fashion weeks and fashion’s creative class.

The Hood By Air co-founder’s ready-to-wear capsule for the Paris-based perfume and fashion house will be timed to coincide with the Met Gala in New York.

Revenues fell on a reported basis, confirming sector-wide fears that luxury demand would continue to slow.

IWC’s chief executive says it will keep leaning into its environmental message. But the watchmaker has scrapped a flagship sustainability report, and sustainability was less of a focus overall at this year’s Watches and Wonders Geneva.

The larger-than-life Italian designer, who built a fashion empire based on his own image, died in Florence last Friday.