The Business of Fashion

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Agenda-setting intelligence, analysis and advice for the global fashion community.

Shein, the fast-fashion empire built on unbranded $5 tops and $18 dresses pumped out by anonymous factories in China, has quietly gotten into the business of selling Stuart Weitzman heels, Coach purses, Lanvin sneakers and Paul Smith shirts, too.

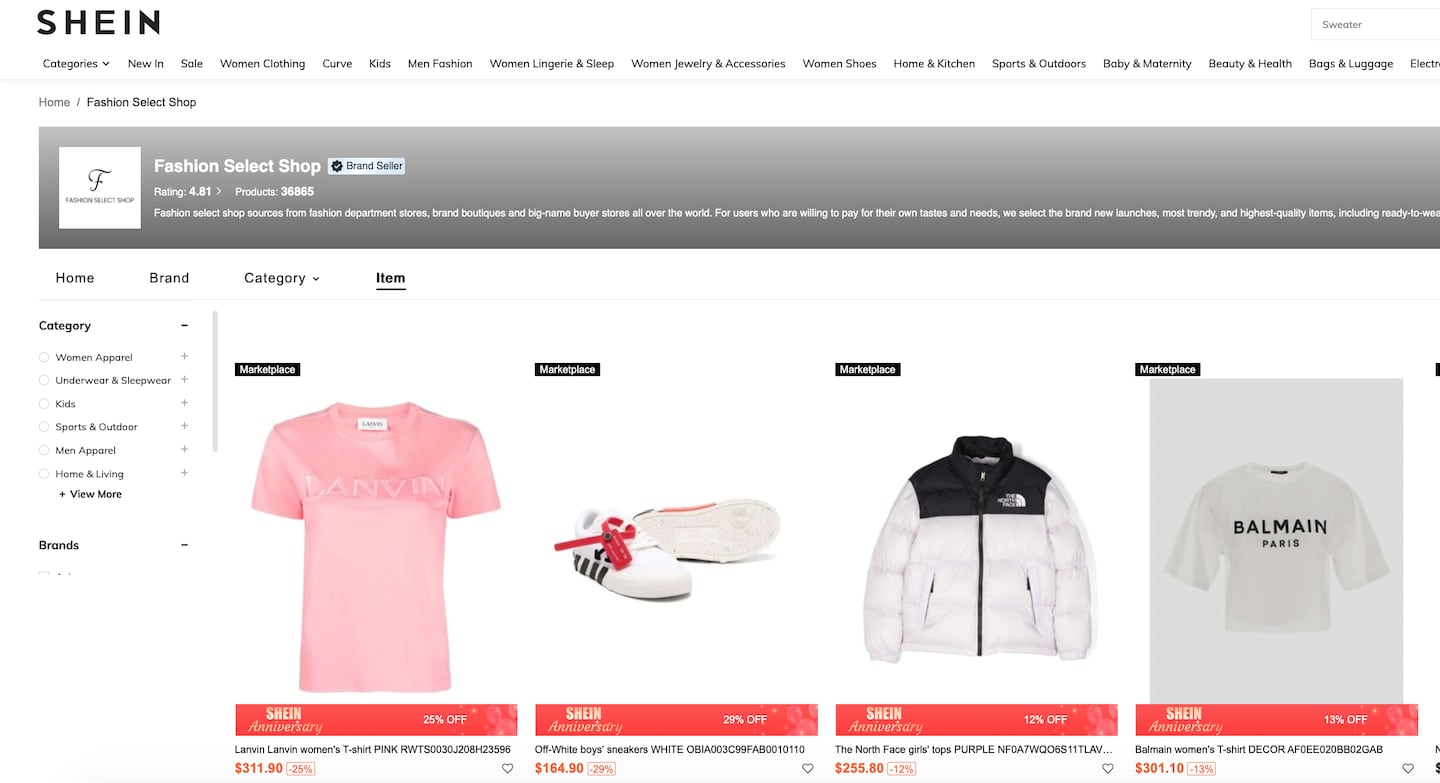

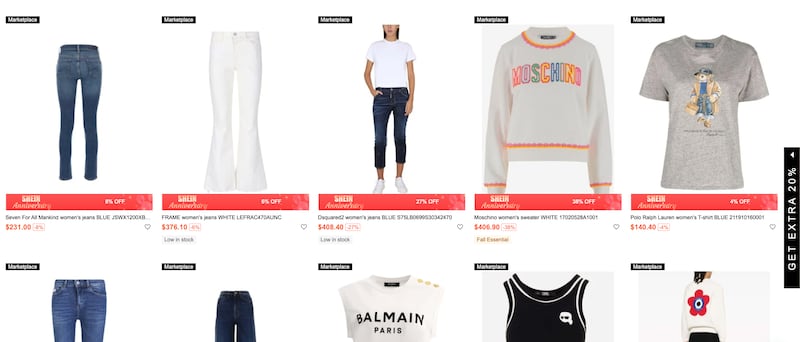

Since the company opened its website and app to third-party sellers in May, Shein has been flooded with listings for luxury goods. One seller, Fashion Select Shop, lists over 24,000 items, from $17 Carhartt socks to a bedazzled Maison Margiela handbag for $1,770 (23 percent off retail, the seller claims).

Generally, the items appear to be new, though it’s not clear whether they are authentic, or how they came to be for sale on Shein. The Singapore-based e-tailer has signed partnerships to sell products from Skechers, Hanes and a handful of other brands. But BoF could not find any luxury labels that had authorised their goods to be listed on Shein’s site or app.

“We do not supply them with stock nor sell directly via them as a marketplace,” a Paul Smith spokesperson told BoF. A Lanvin spokesperson said, “We do not and cannot confirm the authenticity of these products.” Coach, Stuart Weitzman and other brands with items listed on Shein did not return requests for comment.

ADVERTISEMENT

Luxury brands tend to be picky about which retailers they allow to sell their goods. They don’t want to see their products heavily discounted, sold alongside knockoffs or posted in an unflattering way. Legally they have little recourse though, as long as a third-party seller acquired their merchandise legitimately.

The listings are a double-edged sword for Shein, however. The retailer wants to be known for more than ultra-cheap fast fashion, which helped it quickly gain traction with young shoppers. But the strategy may be reaching its limits, especially in the US, its biggest market, where Shein faces competition in the race to the bottom from Temu, Walmart, Amazon and other retail giants.

Selling branded, higher-priced products is one way to bring in wealthier and older customers. However, if Shein wants to copy the Amazon and Alibaba model, convincing well-known brands to set up shop alongside anonymous sellers, the unauthorised luxury listings may pose a roadblock.

“It will absolutely affect [Shein] in a negative way if they are sourcing the product in an unauthorised manner through third parties,” said Michael Prendergast, managing director at Alvarez & Marsal Consumer Retail Group. “Brands could and most likely will be punitive with them.”

Brands regularly send merchandise that fails to sell in-season to discount retailers like T.J. Maxx, or resale sites. These retailers will likely put the items on severe markdown, but they’ll do so relatively discreetly. If brands are dumping merchandise with Shein, they are unlikely to talk about it, given the retailer’s association with rock-bottom prices and status as a lightning rod for critics on social media.

But brands can’t always control where their merchandise is sold. There is a vast “grey market” of new goods that were never authorised for resale. On an individual level, tourists often take advantage of regional price differences and fluctuating exchange rates to buy products cheaply abroad and sell them for a markup at home (in China, this practice, known as daigou, takes place on a massive scale). The strong dollar creates plenty of opportunities for this sort of arbitrage in the US.

Suppliers to luxury brands have also been known to do side deals in the grey market; that can mean selling unbranded “dupes” of popular products, which are often legal and have exploded in popularity thanks to social media. However, fake and stolen goods can also be laundered through the grey market.

“It’s possible that there are factories either producing very good quality counterfeits or nominated factories selling unauthorised overruns, or less than first quality of the product to them,” said Prendergast.

ADVERTISEMENT

A Shein representative said the company vets all third-party sellers with “a thorough review of the seller’s brand portfolio, product selection, and customer service ratings.” Merchants sign an agreement that includes terms on intellectual property infringement.

Not much, according to Susan Scafidi, founder and director of the Fashion Law Institute at Fordham Law School.

“Under the first sale doctrine in the US, once goods are placed in the stream of commerce, brands have little control over their resale… as long as the goods are genuine, their sale is usually legal,” she said.

Brands can take action if a marketplace allows sellers to list fakes, however. Chanel successfully sued Amazon in 2017 over counterfeit goods on its marketplace, and is in an ongoing legal battle with The RealReal.

In 2019, Beautyblender sued a German distrubutor after its makeup removal sponges appeared on shelves at Costco and T.J. Maxx. It claims the distributor broke the terms of its contract by supplying products to a third distributor.

Legal threats alone can’t stop the flood of counterfeits, let alone legitimate merchandise that’s sold legally, albeit by retailers the brands haven’t agreed to work with. Proving legitimate goods were stolen or otherwise improperly sourced is even harder.

“The system isn’t perfect, and the Whac-A-Mole analogy is brand protection professionals’ favourite cliche,” Scafidi said, “but brands also work with online service providers, payment processors, and law enforcement to address trade in counterfeits.”

Shein says it enforces its policies with a combination of image-recognition technology and manual review. Merchants that infringe on IP face possible suspension and termination, and brands can request Shein remove goods they believe to be counterfeit.

ADVERTISEMENT

Marketplaces like Amazon and Alibaba have battled similar issues throughout their history. About a decade ago, both platforms came under heightened pressure from brands to crack down on counterfeit and grey market goods. Kering sued Alibaba in 2015; Birkenstock yanked its inventory from Amazon in 2016, alleging the company wasn’t doing enough to keep fake versions of its popular sandals off the site.

Starting around that time, both e-commerce companies made a public effort to better police their listings, though brands still complain that lookalikes and unauthorised resellers slip through. Those efforts have paid off: Alibaba’s Tmall now hosts hundreds of luxury labels (Kering dropped its lawsuit in 2017 and said it would cooperate with the site on intellectual property issues). In the US, brands such as Adidas, Under Armour and Victoria’s Secret sell on Amazon, though the e-commerce giant has made less headway at the upper end of the market.

Shein is just starting down this road with its Skechers partnership, as well as a deal announced in August with Forever 21.

The company sees moving upmarket as one key to future growth, and will need to attract well-known labels to make its case to shoppers, experts say.

“Brands are probably more in demand than ever, and that a growing number of consumers are seeking brands that resonate with their lifestyles more than undifferentiated … product,” commented Deborah Weinswig, CEO and founder of retail consulting firm Coresight Research.

Online fast fashion juggernaut Shein and SPARC Group — a joint venture between licensing firm Authentic Brands Group and mall operator Simon Property Group — have formed a partnership that could see Forever 21 clothing and accessories sold on Shein’s site, and Shein roll out shop-in-shops inside Forever 21 Stores.

Zoetop Business Co., the Hong Kong-based entity that previously owned Shein, is among the defendants, as is Shein Group Ltd., according to a writ of summons issued in July 2021 and recently obtained by Bloomberg News.

The US Federal Trade Commission filed a long-awaited antitrust lawsuit against Amazon on Tuesday, charging the online retailer with harming consumers through higher prices in the latest US government legal action aimed at breaking Big Tech’s dominance of the internet.

Tiffany Ap is Senior Correspondent at The Business of Fashion. She is based in New York and covers marketing and the critical China market.

Nordstrom, Tod’s and L’Occitane are all pushing for privatisation. Ultimately, their fate will not be determined by whether they are under the scrutiny of public investors.

The company is in talks with potential investors after filing for insolvency in Europe and closing its US stores. Insiders say efforts to restore the brand to its 1980s heyday clashed with its owners’ desire to quickly juice sales in order to attract a buyer.

The humble trainer, once the reserve of football fans, Britpop kids and the odd skateboarder, has become as ubiquitous as battered Converse All Stars in the 00s indie sleaze years.

Manhattanites had little love for the $25 billion megaproject when it opened five years ago (the pandemic lockdowns didn't help, either). But a constantly shifting mix of stores, restaurants and experiences is now drawing large numbers of both locals and tourists.